Climate crises Q&A: Why have some recent storms gained so much strength, so quickly?

Warming oceans and the El Nino phenomenon have caused some storms to gain strength far more rapidly than predicted. When communities are caught off-guard, the results can be devastating. More investment in forecasting, early warning, preparation — and an assist from artificial intelligence — are parts of the solution.

An interview with Juan Bazo, climate scientist with the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, by Susana Arroyo Barrantes, IFRC Americas Regional Communications Manager. Originally published on the IFRC website.

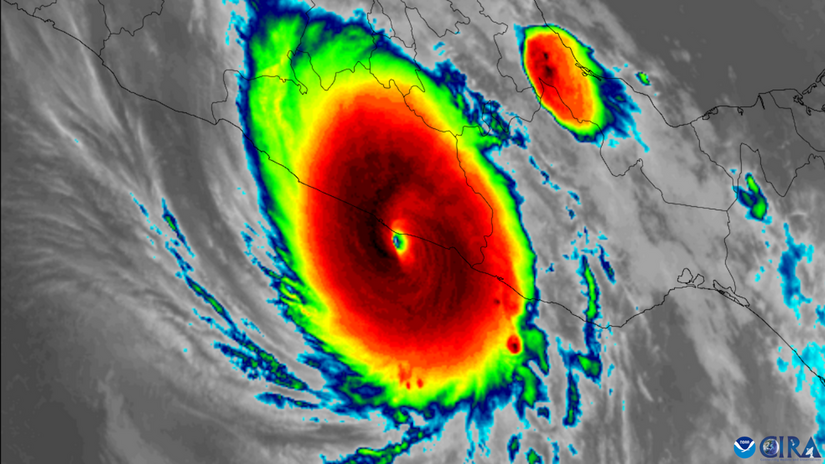

Susana Arroyo: In October 2023, Hurricane Otis caused a lot of astonishment after it went from a tropical storm to a category 5 hurricane in just 12 hours. According to the U.S. National Hurricane Center, it was the most powerful hurricane ever recorded on the Mexican Pacific coast. Did El Niño have something to do with the rapid intensification of Otis?

Juan Bazos: It was a combination of warm oceans, along with El Niño. In addition, the entire Pacific coastline of Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, and the coasts of Costa Rica, have been very warm. This has allowed the formation of cyclones and storms. Some of these storms have even passed from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Regarding the intensification, this has happened before, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, also had this very rapid intensification in less than 12 hours off the Pacific coast of Mexico, but the impact was not in a very populated area.

For a scientific point of view, it is increasingly difficult to forecast this type of intensification. Most, if not all, of the models failed in the short-term forecast, which is one of the most reliable forecasts we have in meteorology. This is due to several factors: the rapid intensification, very local atmospheric conditions, and the temperature of the ocean water in this part of the Mexican coast.

Increasingly, intensification is not only occurring in the Pacific and Atlantic of our region, but also in the Indian Ocean. In The Philippines, this has happened many times. That is a challenge, both for the climate services and for the humanitarian response.

SA: One thing we depend on to make life-saving decisions is rigorous, accurate, effective forecasts. If we are moving towards an era of greater uncertainty, then we must also look at how we anticipate on other fronts. What can we expect for this year?

JB: In the following months, we would normally be entering a neutral period and quickly passing to La Niña phenomenon. And this will also bring its consequences, changing the whole panorama. It could be that this year we will have to prepare for a hurricane season that may be higher than normal. So, we must keep monitoring, considering the climate crisis and the Atlantic Ocean that is still very warm.

SA: The IFRC has tried to make more alliances with meteorological institutions dedicated to researching, monitoring, and understanding the climate. Is that one of the paths to the future, to strengthen this alliance?

JB: Increasingly, the IFRC has scientific technical entities as its main allies, to make reliable decisions, and I think that is the way we must continue to work. Scientific information will bring us information for our programs and operations at different time scales, in the short, medium, and long term. We must not ignore climate projections but plan how we can adapt knowing that the climate is going to change. This is part of our work, from our policies to our interventions and I think the Red Cross and Red Crescent network does this very well.

However, we need to empower ourselves more, get closer to the technical scientific entities, the academia, which are our allies. They can bring us much more information — much richer, much more localized. And this is the next step we must take.

SA: Many changes are also coming in the field of meteorology. Now, using artificial intelligence (AI) and increasingly large amounts of data, there will be changes and likely improvements in forecasting. Could we therefore get more reliable forecasts in terms of rapid intensification?

JB: Artificial Intelligence opens a lot of room for innovation. Meteorology is not 100 per cent accurate. There is always that degree of uncertainty and there are going to be failures. It is part of our planet's atmospheric chaos, of its complexity and the many variables that play a role in weather forecasting. In that sense, AI will be a great added value for the improvement of forecasts.

This brings to the table the need for 1) greater investment in forecast-based early action systems, 2) early warning systems that are more agile, flexible, and capable of informing and mobilizing the population in record time, and 3) humanitarian aid that is pre-positioned to respond to disasters as they occur.